Wilson’s Disease: Understanding Copper Accumulation and Chelation Therapy

Jan, 27 2026

Jan, 27 2026

Wilson’s disease isn’t something most people have heard of-until it hits their family. It’s rare, affecting about 1 in 30,000 people, but if left untreated, it’s deadly. The problem isn’t eating too much copper-it’s your body’s inability to get rid of it. This isn’t a diet issue. It’s a genetic flaw that turns copper from a necessary nutrient into a silent poison. And the damage builds up slowly, often without symptoms, until your liver or brain starts failing.

How Copper Turns Against You

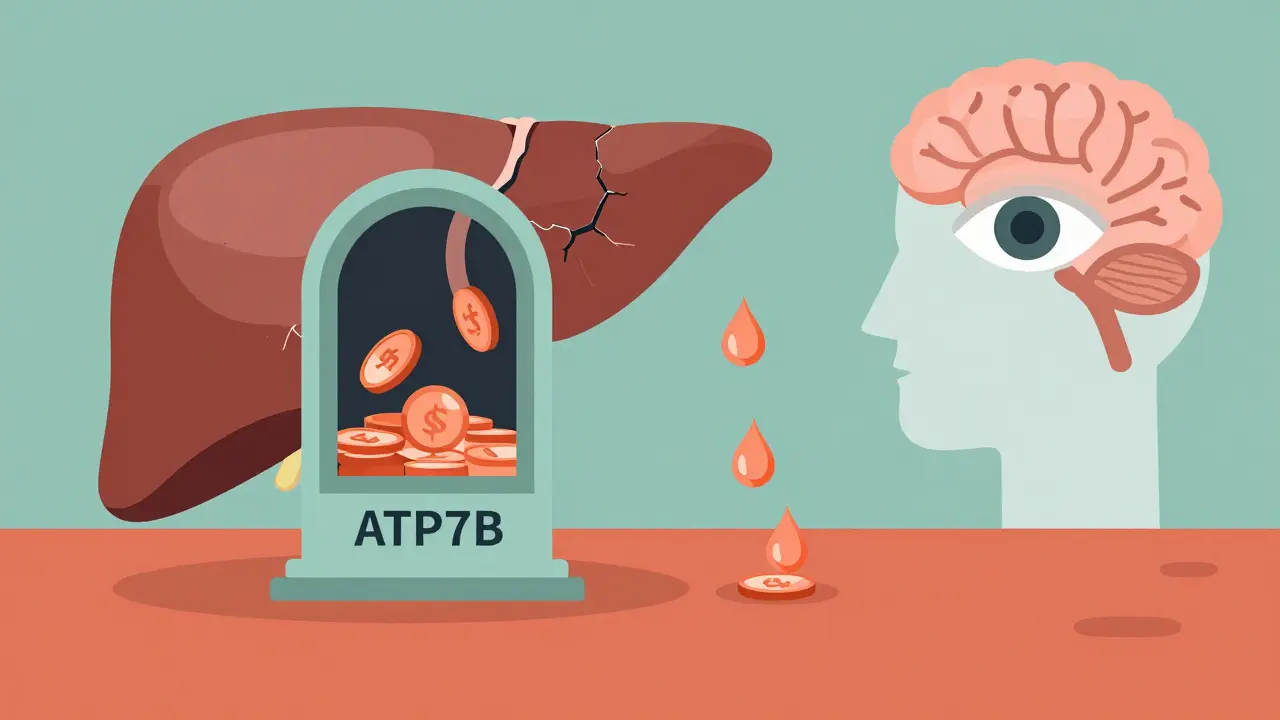

Your body needs copper. It helps make red blood cells, keeps nerves working, and supports your immune system. But your liver is the gatekeeper. Normally, it uses a protein called ATP7B to lock copper onto ceruloplasmin (so it can travel safely in your blood) and push the extra out through bile. In Wilson’s disease, the ATP7B gene is broken. The protein doesn’t work. Copper piles up in the liver first.

At first, your liver tries to cope. Metallothionein, a natural copper sponge, soaks up the excess. But after years, it gets full. Then copper leaks into your bloodstream as free copper-unbound, toxic, and free to roam. It doesn’t take long for it to settle in the wrong places: your brain, especially the basal ganglia, your eyes (forming greenish-brown Kayser-Fleischer rings around the iris), and your kidneys.

That’s why symptoms show up so differently. Some people get liver problems first-fatigue, jaundice, belly pain. Others start with tremors, stiff muscles, trouble speaking, or even depression. A 15-year-old might be misdiagnosed with ADHD. A 28-year-old with unexplained liver enzyme spikes might be told they have autoimmune hepatitis. The average delay in diagnosis? Nearly three years. By then, damage is often already done.

Diagnosing the Invisible

There’s no single test for Wilson’s disease. Doctors piece it together. Serum ceruloplasmin is usually below 20 mg/dL (normal is 20-50). Urinary copper over 24 hours? Above 100 μg is a red flag-though in neurological cases, it can be lower. A slit-lamp eye exam can spot Kayser-Fleischer rings in 95% of people with brain symptoms. Liver biopsy showing copper levels over 250 μg/g dry weight confirms it.

But here’s the catch: kids under five often don’t have the rings, and their ceruloplasmin can be low for other reasons. That’s why genetic testing for ATP7B mutations is now part of the official diagnostic score. If you have two confirmed mutations, you don’t need all the other signs. It’s definitive.

And you can’t rely on routine blood work. A normal ALT or AST doesn’t rule it out. That’s why so many people are misdiagnosed. One Reddit user spent seven years being treated for autoimmune hepatitis before a 24-hour urine test showed 380 μg of copper-clear proof of Wilson’s.

Chelation Therapy: Pulling Out the Poison

Once diagnosed, treatment starts fast. The goal isn’t to remove all copper-it’s to stop the buildup and let your body slowly clear the excess. That’s where chelation comes in.

D-penicillamine was the first drug approved for this in 1956. It binds copper and lets your kidneys flush it out. But it’s rough. Up to half of patients get worse before they get better-neurological symptoms spike in the first few weeks. Side effects include rashes, kidney damage, and even lupus-like reactions in 22% of users.

Trientine is the next option. It’s gentler on the brain and doesn’t cause as many neurological flares. But it costs nearly six times more than penicillamine-around $1,850 a month in the U.S. Many patients can’t afford it without insurance.

Then there’s zinc. Not a chelator, but a shield. Zinc acetate makes your gut produce metallothionein, which traps copper from food so it can’t be absorbed. It’s used for maintenance after initial chelation, or for people with mild symptoms. It’s cheaper-about $450 a month-and has fewer side effects. But it doesn’t pull copper out of your liver or brain. It only stops more from coming in.

That’s why treatment is layered. Most people start with penicillamine or trientine, then switch to zinc once copper levels drop. And you can’t stop. Ever. One missed dose can let copper creep back up. The Wilson Disease Foundation found that 35% of patients miss doses regularly-often because of nausea, metallic taste, or just the sheer complexity of taking pills three times a day on an empty stomach.

What You Can’t Ignore: Diet and Lifestyle

Chelation works better if you cut back on copper-rich foods. That means avoiding liver, shellfish, nuts, chocolate, mushrooms, and whole grains. Even tap water from copper pipes can add up. The goal is under 1 mg of copper per day.

But here’s the problem: cutting out these foods can leave you short on other nutrients. Iron, zinc, B vitamins-you need them too. Many patients end up with iron deficiency, especially on trientine. That’s why regular blood tests aren’t optional. You need to check not just copper, but hemoglobin, ferritin, and liver enzymes every few months.

One patient switched from penicillamine to zinc after kidney damage. His ALT dropped from 145 to 38 in six months. He still eats carefully, but he’s stable. No tremors. No new symptoms. He’s 42 now. He’s alive because he stuck with it.

New Hope on the Horizon

There’s progress. In 2023, a new drug called CLN-1357-a copper-binding polymer-showed an 82% drop in free copper in just 12 weeks, with zero neurological worsening. Another drug, WTX101 (bis-choline tetrathiomolybdate), got breakthrough status from the FDA after it prevented neurological decline in 91% of patients-better than trientine’s 72%.

And gene therapy is starting. Early trials are injecting a working copy of the ATP7B gene into the liver using harmless viruses. Six patients so far. No serious side effects. It’s early, but if it works, it could mean one-time treatment instead of lifelong pills.

But these aren’t available everywhere. In low-income countries, diagnosis delays still stretch past five years. Many people never get treated at all. Even in the U.S., only 65% of patients get guideline-recommended care. Cost, access, and awareness are still huge barriers.

Living with Wilson’s Disease

Wilson’s disease isn’t a death sentence anymore. With early diagnosis and consistent treatment, life expectancy is normal. But it’s not easy. It’s daily pills. Regular blood tests. Constant vigilance. It’s explaining to friends why you can’t eat cashews or shellfish. It’s the fear that one missed dose could undo years of progress.

But it’s also hope. People are living into their 60s, 70s, even 80s. They’re working, raising kids, traveling. They’re on zinc. They’re on trientine. They’re on new drugs still in trials. They’re surviving because they didn’t give up.

If you or someone you know has unexplained liver problems, neurological symptoms, or a family history of early liver disease, ask for a Wilson’s disease test. It’s simple: urine copper, ceruloplasmin, eye exam, genetic test. No big surgery. No invasive scans. Just a few tests that can change everything.

Because Wilson’s disease doesn’t care how old you are, how healthy you think you are, or how little you know about copper. It waits. And then it strikes. But it can be stopped. If you catch it early enough.

Can Wilson’s disease be cured?

No, Wilson’s disease cannot be cured-but it can be managed for life. With consistent chelation therapy, zinc supplementation, and dietary control, copper levels can be kept low enough to prevent organ damage. Patients who start treatment early and stick with it can live normal lifespans. Gene therapy is being studied as a potential one-time cure, but it’s still experimental.

What happens if you stop chelation therapy?

Stopping treatment causes copper to build up again, often rapidly. Even a few weeks without medication can lead to liver failure or neurological decline. In some cases, symptoms return worse than before. Wilson’s disease requires lifelong therapy. There is no safe pause or break.

Why does D-penicillamine make neurological symptoms worse?

D-penicillamine pulls copper out of the liver and into the bloodstream before it can be fully excreted. This temporary spike in free copper can cross the blood-brain barrier and worsen brain symptoms. That’s why doctors often add zinc at the start-to block new copper absorption-and monitor closely. Trientine is less likely to cause this spike, which is why it’s preferred for patients with neurological symptoms.

Can Wilson’s disease show up after age 40?

Yes. While most cases appear between ages 5 and 35, about 10% of patients are diagnosed after 40. Late-onset cases often present with liver problems rather than neurological symptoms. If you have unexplained cirrhosis or elevated liver enzymes after 40 with no other cause, Wilson’s disease should be ruled out-even if you have no family history.

Is genetic testing necessary for diagnosis?

It’s not always required, but it’s highly recommended. Finding two mutations in the ATP7B gene confirms Wilson’s disease with near 100% certainty. This is especially helpful when symptoms are unclear, ceruloplasmin is borderline, or Kayser-Fleischer rings are absent. Genetic testing also helps identify carriers in the family, allowing early screening for siblings or children.

How often do you need blood and urine tests?

During active treatment, liver function tests are done every 3 months. Urinary copper is checked every 6 months to ensure it’s between 200-500 μg/24h (the target for copper removal). Serum free copper should be monitored every 3 months and kept below 10 μg/dL. Once stable, tests can be reduced to every 6-12 months, but never stopped.

Can you drink alcohol with Wilson’s disease?

No. Alcohol stresses the liver, which is already struggling to manage copper. Even small amounts can speed up liver damage and increase the risk of cirrhosis or liver failure. Complete abstinence is recommended for all patients, regardless of how early the disease was caught.

What foods should be avoided in Wilson’s disease?

Avoid high-copper foods: liver, shellfish (especially oysters), mushrooms, nuts (cashews, hazelnuts), chocolate, soy products, whole grains, and dried fruit. Also avoid cooking with copper pots or drinking water from copper pipes. Most patients aim for less than 1 mg of copper per day. A dietitian familiar with Wilson’s disease can help create a balanced, low-copper meal plan.

If you’re on treatment, stay consistent. If you suspect you or someone you know might have Wilson’s, don’t wait. Get tested. Copper doesn’t care how busy you are. But you can still beat it-if you act.