STIs Overview: Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Syphilis Management

Jan, 4 2026

Jan, 4 2026

When it comes to bacterial sexually transmitted infections, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis are the most common - and the most dangerous if left untreated. In 2021, the U.S. reported over 2.5 million cases of just these three infections. Half of them were in people under 25. What’s worse? Most of these cases show no symptoms at all. You can have chlamydia and not know it for months, even years, while it silently damages your reproductive system. That’s why understanding how these infections work - and how to treat them - isn’t just medical knowledge. It’s survival.

What You Need to Know About Chlamydia

Chlamydia is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, and it’s the most reported bacterial STI in the U.S. and globally. The CDC estimates 129 million new cases worldwide every year. It spreads through vaginal, anal, or oral sex. But here’s the catch: up to 95% of women and half of men show no symptoms. That’s why routine screening is critical, especially for sexually active people under 25.

When symptoms do appear, they’re often mild. Women might notice abnormal discharge, pain during urination, or bleeding between periods. Men may have a burning sensation when peeing or a clear or milky discharge from the penis. Rectal infections can cause pain, discharge, or bleeding - often mistaken for hemorrhoids.

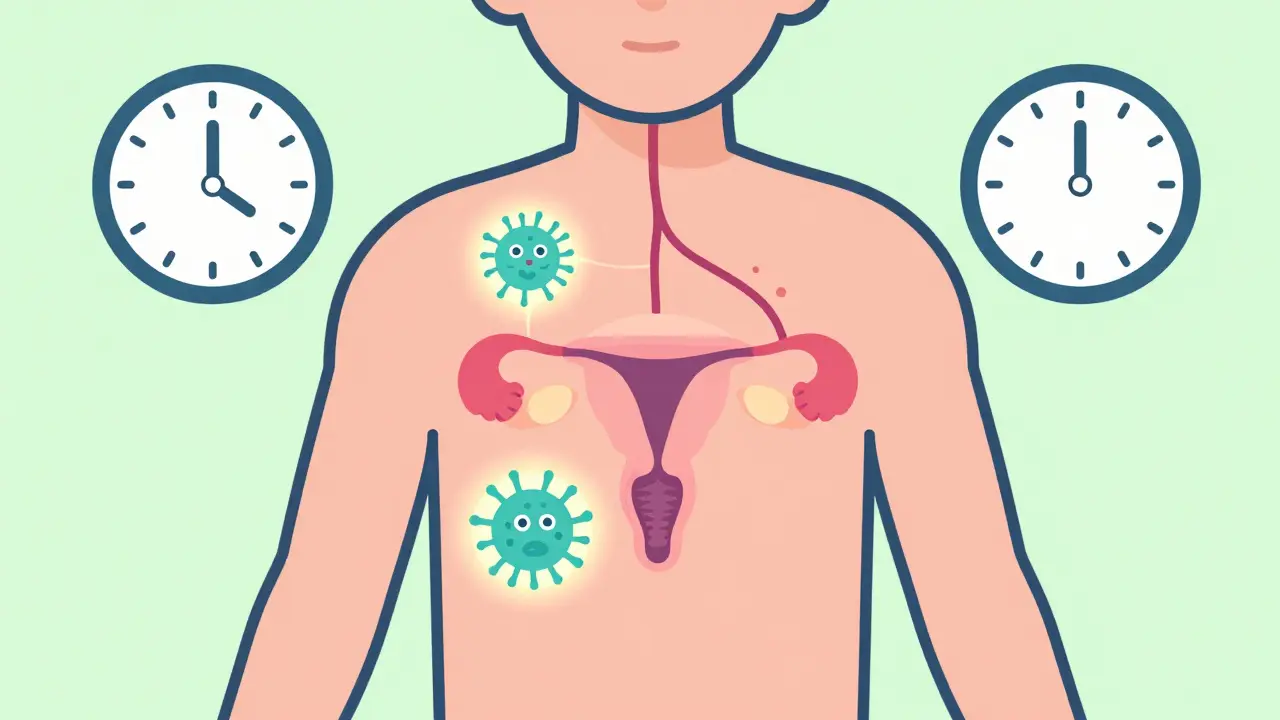

Left untreated, chlamydia can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in 10-15% of women. PID scars the fallopian tubes, which can cause infertility or ectopic pregnancy - where a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus, a life-threatening condition. It also increases your risk of contracting HIV by two to three times.

Treatment is simple if caught early: a single dose of azithromycin (1 gram) or a week of doxycycline (100 mg twice daily). Cure rates are above 95%. But reinfection is common - about 1 in 5 young women get chlamydia again within a year. That’s why retesting at 3 months is standard. And if you’re treated, your partner must be treated too. Otherwise, you’ll pass it back and forth.

Gonorrhea: The Resistant Threat

Gonorrhea, caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, is the second most common bacterial STI. It’s also the most dangerous because it’s becoming harder to treat. The CDC calls it an “urgent threat” due to rising antibiotic resistance. In some areas, up to half of gonorrhea strains are now resistant to azithromycin, one of the two drugs we’ve relied on for years.

Symptoms are similar to chlamydia: discharge, burning during urination, pain in the rectum. But gonorrhea is more likely to spread beyond the genitals. About 1 in 50 people develop disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), which causes joint pain, skin sores, and fever - and can be fatal if not treated fast.

Testing is easy: a urine sample or swab from the throat, rectum, or cervix. But treatment? It’s changed dramatically. The current CDC protocol is a one-time shot of ceftriaxone (500 mg) plus a single oral dose of azithromycin. This dual therapy is still effective for now - but only just. Doctors are watching closely. If resistance keeps rising, we might run out of options.

There’s good news on the horizon: a new drug called zoliflodacin, tested in phase 3 trials with 96% success, is expected to get FDA approval by 2025. It’s the first new gonorrhea antibiotic in decades. Until then, prevention is your best defense. Condoms reduce transmission by 60-90%. And if you’ve had condomless sex, especially with multiple partners, talk to your doctor about doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (DoxyPEP). Studies show it cuts gonorrhea risk by up to 73% in men who have sex with men and transgender women on PrEP.

Syphilis: The Great Imitator

Syphilis is different. It doesn’t just cause discharge or pain. It creeps through your body in stages, sometimes for years, mimicking other diseases. That’s why it’s called the “great imitator.”

Stage one: a single, painless sore - called a chancre - appears 10 to 90 days after exposure. It heals on its own, so many people don’t realize they’re infected. Stage two: weeks to months later, you might get a rash on your palms or soles, fever, swollen lymph nodes, or patchy hair loss. Again, these can disappear without treatment.

Then comes the silent phase - latent syphilis. You feel fine. No symptoms. But the bacteria are still in your blood. Years later, untreated syphilis can attack your heart, brain, nerves, and eyes. This is tertiary syphilis. It can cause stroke, dementia, blindness, or death.

Diagnosis is always through blood tests. No urine swabs here. Treatment depends on how long you’ve had it. Early syphilis (under a year) gets one shot of benzathine penicillin G (2.4 million units). Late syphilis? Three shots, one per week. If you’re allergic to penicillin, alternatives exist - but they’re less reliable.

Here’s the alarming part: congenital syphilis is surging. Between 2017 and 2021, cases in newborns jumped 273% in the U.S. That’s because many pregnant women aren’t being screened. The CDC now recommends testing all pregnant women at first prenatal visit - and again at 28 weeks in high-risk areas. If caught early, syphilis in pregnancy can be cured with penicillin, preventing stillbirth, brain damage, or death in the baby.

Testing, Partner Notification, and Follow-Up

You can’t treat what you don’t find. That’s why testing matters. For chlamydia and gonorrhea, a urine test is accurate and non-invasive. For syphilis, it’s a blood draw. If you’ve had oral sex, ask for throat and rectal swabs - gonorrhea hides there often.

When you’re diagnosed, you need to tell your partners. The CDC says anyone you’ve had sex with in the past 60 days (for chlamydia and gonorrhea) or up to 90 days (for syphilis) should be treated - even if they feel fine. Health departments can help you notify them anonymously.

Retesting is non-negotiable. For chlamydia, get tested again at 3 months. For gonorrhea, if you had a throat infection, get a test-of-cure after treatment because failure rates are higher there. Syphilis requires blood tests every 3-6 months for a year to make sure the infection is clearing.

Prevention: More Than Just Condoms

Condoms reduce chlamydia and gonorrhea transmission by 60-90% and syphilis by 50-70%. But they’re not foolproof - especially during oral sex. That’s why DoxyPEP is a game-changer for high-risk groups. Taking a single 200 mg pill of doxycycline within 72 hours after condomless sex can slash your risk of all three STIs.

But it’s not for everyone. Studies show it doesn’t work for cisgender women. And doctors worry about promoting antibiotic resistance if it’s used too widely. So right now, it’s recommended only for men who have sex with men and transgender women on PrEP.

Still, the biggest barrier isn’t medicine - it’s stigma. Many people avoid testing because they’re embarrassed. Or they think, “I’m not promiscuous, so I’m fine.” But STIs don’t care about your relationship status. One unprotected encounter is all it takes.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

The U.S. spends over $16 billion a year treating STIs. Chlamydia alone costs $500 million annually. But the real cost is in lives - infertility, newborn deaths, HIV transmission, and chronic illness.

Racial disparities are stark. Black Americans are 5-7 times more likely to get chlamydia or gonorrhea than white Americans. That’s not about behavior - it’s about access to care, testing, and education.

Global efforts are ramping up. The WHO wants to cut syphilis in pregnant women by 90% and chlamydia/gonorrhea by 70% by 2030. But without better screening, faster diagnostics, and new antibiotics, we’re losing ground.

The message is simple: get tested regularly. If you’re sexually active, get screened at least once a year. If you have new or multiple partners, get tested every 3-6 months. Tell your partners. Use condoms. And if you’ve had unprotected sex, ask about DoxyPEP - if you’re in a group it works for.

These infections are treatable. But they’re not harmless. And they don’t vanish on their own. The only way to stop them is to face them - early, honestly, and without shame.

Can you get chlamydia or gonorrhea from a toilet seat?

No. Chlamydia and gonorrhea bacteria can’t survive long outside the human body. They need moist mucous membranes to live - like those in the genitals, rectum, or throat. Toilet seats, towels, or hot tubs won’t transmit them. Transmission requires direct sexual contact.

If I’m treated for syphilis, will I always test positive?

Yes, but it depends on the test. Treponemal tests (like the RPR or TPPA) detect antibodies that stay in your blood for life, even after cure. That means you’ll always test positive on those. But non-treponemal tests (like the VDRL) measure active infection. After successful treatment, these should drop and eventually become negative or very low. Your doctor will track these levels over time to confirm the infection is gone.

Can you have syphilis and not know it for years?

Absolutely. After the initial sores and rash fade, syphilis enters a latent phase - sometimes for decades. You feel fine. No symptoms. But the bacteria are still active in your body, quietly damaging organs. That’s why routine blood testing is critical, especially for people with multiple partners or those who’ve had unprotected sex in the past.

Why is gonorrhea harder to treat than chlamydia?

Gonorrhea has developed resistance to nearly every antibiotic we’ve thrown at it - from penicillin to ciprofloxacin to azithromycin. It mutates quickly and shares resistance genes easily. Chlamydia hasn’t developed widespread resistance yet, so doxycycline and azithromycin still work well. But gonorrhea is evolving faster than our drug pipeline, which is why new treatments like zoliflodacin are so urgent.

Is DoxyPEP safe for everyone?

No. DoxyPEP is only recommended for men who have sex with men and transgender women on PrEP. Studies show it reduces STI risk by 47-73% in these groups. But in cisgender women, trials found no significant benefit. Also, using it broadly could drive antibiotic resistance. It’s not a substitute for condoms or regular testing - it’s a targeted tool for high-risk populations.

Wesley Pereira

January 5, 2026 AT 14:54Bro, gonorrhea’s got more antibiotic resistance than my ex had excuses. CDC’s panic mode is real - we’re one bad mutation away from walking into a post-antibiotic apocalypse where a UTI kills you. And zoliflodacin? If it works, it’s the first real win since penicillin. But let’s be real - most people still think STIs are ‘someone else’s problem.’

Tiffany Adjei - Opong

January 7, 2026 AT 14:07Wait, so you’re telling me DoxyPEP works for gay men and trans women but not cis women? That’s not prevention - that’s medical discrimination. Why are we treating bodies like they’re different operating systems? If it’s safe for one group, why not all? And don’t give me that ‘antibiotic resistance’ excuse - we’ve had condoms for 50 years and people still don’t use them. This feels like blaming the victim again.

Isaac Jules

January 8, 2026 AT 12:22Chlamydia’s the silent killer, sure. But let’s not act like everyone’s just waiting to get screwed over. I’ve had 3 partners in 5 years. Tested every 6 months. Used condoms. Still got chlamydia once. Turns out my ex lied. Not my fault. Not hers. Just biology being a dick. Testing isn’t optional - it’s the bare minimum. Stop acting like it’s a moral failure.

Pavan Vora

January 10, 2026 AT 00:41Actually, in India, we have a different problem - people think STIs are only from 'bad' people, so they never get tested. My cousin had syphilis for 3 years, thought it was a rash. Now he’s on treatment, but his liver is damaged. We need education, not just pills. And yes, penicillin is cheap here - but clinics are far away. And people are scared. So they wait. And wait. And wait...

Joann Absi

January 11, 2026 AT 20:37STOP WITH THE ‘JUST USE CONDOMS’ NARRATIVE 😤 This isn’t 1995! We’re in 2025 and people are still treating STIs like a punishment? I’m not promiscuous, I’m just… alive. And now I’m supposed to take a pill after every hookup like it’s a snack? And what about people who can’t afford testing? Or don’t have insurance? This whole system is rigged. 💔💉 #STIsDontCareAboutYourMorals

Ashley S

January 13, 2026 AT 10:05Why are we even talking about this? Just don’t have sex if you’re scared. Problem solved. 😒

Gabrielle Panchev

January 14, 2026 AT 16:55Let’s not ignore the structural failures here: the fact that Black communities are five to seven times more likely to be diagnosed with chlamydia isn’t because they’re having more sex - it’s because clinics are underfunded, providers are biased, and public health campaigns don’t reach them. And yes, DoxyPEP is a tool, but it’s a Band-Aid on a broken system. We need universal testing access, not just targeted prophylaxis for privileged demographics. And the WHO’s 2030 goals? Beautiful on paper. But without funding, political will, and community trust? It’s just a PowerPoint slide with a pretty graph.

Katelyn Slack

January 15, 2026 AT 14:19Just wanted to say - I got chlamydia last year. Didn’t know. No symptoms. Got treated. Told my partner. We both got tested. It’s not a big deal. Seriously. Stop acting like it’s a death sentence. Just get tested. It’s a 5-minute urine test. I promise, your future self will thank you. 😊