Organ Transplant Recipients: Immunosuppressant Drug Interactions and Side Effects

Dec, 25 2025

Dec, 25 2025

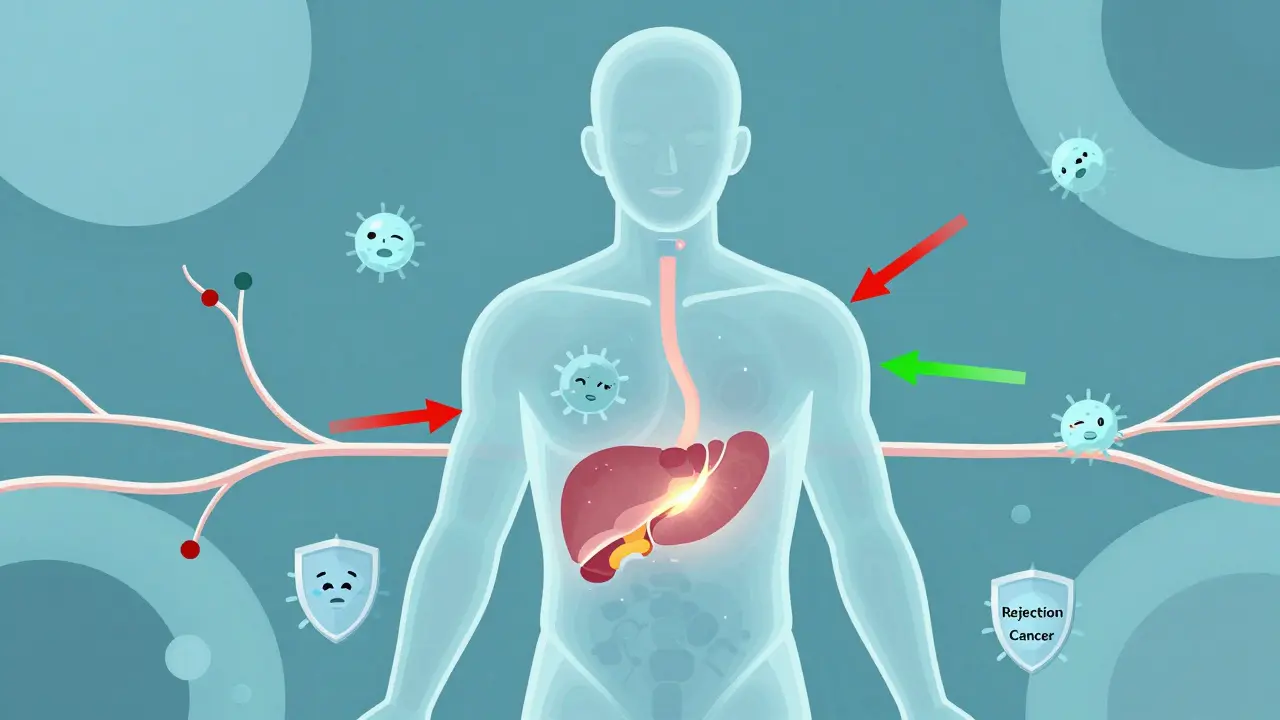

After an organ transplant, taking immunosuppressant drugs isn’t optional-it’s life-saving. These medications stop your immune system from attacking the new organ. But they don’t just protect the transplant. They change how your whole body works. And that comes with serious trade-offs.

How Immunosuppressants Work and Why They’re Necessary

Your body sees a transplanted organ as an invader. Without drugs to calm it down, rejection happens fast. That’s why nearly all transplant recipients take immunosuppressants for life. The only exceptions? Identical twins. Everyone else needs these drugs.

Today’s standard treatment is a triple combo: a calcineurin inhibitor (like tacrolimus or cyclosporine), an antimetabolite (usually mycophenolate mofetil), and a corticosteroid (like prednisone). This mix is powerful. It keeps rejection rates below 10% in the first year. But it’s also complex. Each drug targets a different part of the immune system.

Tacrolimus blocks T-cells from activating. Mycophenolate stops white blood cells from multiplying. Prednisone damps down inflammation across the board. Together, they’re effective. But they’re also toxic. And they don’t just affect your immune system-they mess with your kidneys, liver, metabolism, and even your mood.

Common Side Effects You Can’t Ignore

Side effects aren’t rare. They’re the norm. A 2022 survey of over 1,200 transplant recipients found that 65% deal with at least three ongoing side effects. The most common? High blood pressure (78%), high cholesterol (62%), and diabetes (35%).

Calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus are linked to kidney damage. Up to 40% of kidney transplant patients show signs of chronic kidney injury within five years. That’s not just a lab number-it means more dialysis, more hospital visits, and a higher chance of needing another transplant.

Corticosteroids are the biggest culprit behind metabolic problems. They cause weight gain-often 15 to 20 pounds in the first six months. They lead to moon face, buffalo hump, and thinning skin. One patient on Reddit described staring at their reflection and not recognizing themselves. That’s not vanity-it’s a psychological toll.

Mycophenolate mofetil causes nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea in up to 50% of users. Some people can’t keep food down. Others get severe abdominal pain. It’s not mild discomfort. It’s debilitating. And it’s why many switch to azathioprine, even though that drug increases the risk of low white blood cell counts and infections.

Then there’s the cancer risk. Transplant recipients are 2 to 4 times more likely to develop skin cancer. Nonmelanoma skin cancers affect 23% of liver transplant patients. Colon, lung, and HPV-related cancers are also far more common. The immune system isn’t just suppressing rejection-it’s also letting cancer cells slip by unnoticed.

Drug Interactions That Can Kill You

One of the most dangerous things about immunosuppressants? They play poorly with almost everything else.

Tacrolimus and cyclosporine are broken down by the liver enzyme CYP3A4. That means anything that affects this enzyme can cause a deadly spike or crash in drug levels.

Take fluconazole, a common antifungal. It can raise tacrolimus levels by 50% to 200%. That’s not a little adjustment. That’s a trip to the ER for kidney failure or seizures.

On the flip side, rifampin-a drug used for tuberculosis-can slash tacrolimus levels by 60% to 90%. That’s like turning off your transplant’s safety system. Rejection can happen within days.

Even common over-the-counter meds can be risky. St. John’s wort? It lowers tacrolimus levels. Grapefruit juice? It raises them. Antibiotics like erythromycin, antifungals like ketoconazole, and even some heart medications can interfere. That’s why every new prescription, even for a simple sinus infection, needs to be cleared by your transplant team.

Therapeutic drug monitoring isn’t optional. It’s mandatory. Tacrolimus levels are checked twice a week right after transplant, then weekly for months. If your level drops below 5 ng/mL or climbs above 12 ng/mL, you’re in danger. Too low? Rejection. Too high? Toxicity.

Why Some Patients Switch Drugs

Not everyone stays on the same combo forever. Many switch because side effects become unbearable or kidney function declines.

Sirolimus and everolimus are mTOR inhibitors. They don’t damage the kidneys like calcineurin inhibitors. One study showed patients on sirolimus lost only 2.1 mL/min of kidney function per year, compared to 4.3 mL/min on tacrolimus. That’s a big deal.

But sirolimus has its own problems. It causes mouth sores in 25% of users. It raises triglycerides and cholesterol. And it slows wound healing. After a transplant, even a small cut can take weeks to close.

Some patients switch to belatacept, a newer drug that blocks immune signals without affecting the kidneys. Long-term data shows lower rates of heart disease and cancer. But it comes with a catch: higher rejection rates early on. It’s only used for patients who can handle frequent IV infusions and have low rejection risk.

And then there’s voclosporin, approved in 2023. It’s a new calcineurin inhibitor with more stable levels in the blood. Early results show 24% less kidney damage than tacrolimus. It’s not a cure, but it’s a step forward.

Managing Life With These Drugs

Living with immunosuppressants means treating your body like a high-maintenance machine. You take 8 to 12 pills a day, at exact times. Miss one, and your levels drop. Take too much, and your kidneys suffer.

Electronic pill dispensers help. One clinic saw adherence jump from 72% to 89% when patients used them. That’s the difference between keeping your transplant and losing it.

You also need to avoid risks. No raw sushi. No undercooked eggs. No gardening without gloves. Even a simple cold can turn dangerous. Wear a mask in crowds. Wash your hands constantly. Report any fever over 100.4°F immediately.

Regular blood tests are non-negotiable. Monthly CBCs to check for low blood counts. Quarterly lipid panels. Biannual glucose tests to catch diabetes early. Bone density scans every two years because steroids eat away at your bones. One study found 30-40% of heart transplant patients needed bisphosphonates to prevent fractures.

And yes, the emotional toll is real. Fatigue hits 72% of patients. Sleep problems? 68%. Mood swings, anxiety, even “steroid rage”? Common. You’re not weak. You’re fighting a constant internal battle.

The Big Picture: Survival vs. Quality of Life

Here’s the truth: transplant recipients live 20 years less on average than people their age who haven’t had a transplant. The 10-year survival rate for kidney recipients is 65%. For healthy people? 85%.

Why? Because the drugs that save your new organ also wear down your body. They cause heart disease. They cause cancer. They cause diabetes. They cause infections you can’t fight off.

But here’s the other truth: without these drugs, you wouldn’t be alive at all. The trade-off is brutal, but it’s real. And it’s why experts are pushing for tolerance-inducing therapies-ways to teach the immune system to accept the organ without drugs.

Early trials using regulatory T cells have helped 15% of kidney recipients stop all immunosuppressants. That’s not a cure yet. But it’s hope.

For now, the best thing you can do is know your meds. Track your side effects. Talk to your team. Don’t hide symptoms. Don’t skip doses. Don’t take anything without asking. Your transplant isn’t just a surgery-it’s a lifelong commitment. And the drugs? They’re the price of living.

Can I stop taking immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Stopping immunosuppressants-even if you feel great-can cause your body to reject the transplanted organ within days or weeks. Rejection can happen without warning, and once it starts, it’s often irreversible. Over 22% of late graft failures are due to non-adherence. The drugs are not optional. They’re what keeps your organ alive.

What should I do if I start experiencing new side effects?

Report any new symptom to your transplant team immediately. That includes unexplained fatigue, sudden weight gain, mouth sores, tremors, changes in urination, or fever. Some side effects, like high potassium or low white blood cell counts, can be life-threatening if not caught early. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s normal. Your team needs to adjust your meds or run tests.

Are there safer alternatives to tacrolimus?

Yes, but each has trade-offs. Sirolimus and everolimus are less toxic to the kidneys but cause mouth ulcers and high cholesterol. Belatacept avoids kidney damage and lowers cancer risk but requires weekly IV infusions and has higher early rejection rates. Voclosporin is a newer calcineurin inhibitor with fewer kidney side effects. The right choice depends on your organ, your health history, and your tolerance for side effects. There’s no universal “best” drug-only the best for you.

Can I take over-the-counter supplements or herbal remedies?

Almost none are safe. St. John’s wort, echinacea, garlic supplements, and grapefruit juice can all interfere with immunosuppressants. Even vitamin D and calcium can affect absorption. Always check with your transplant pharmacist before taking anything-not just your doctor. Many supplements are not regulated and can cause dangerous drug interactions.

Why do I need to live close to the transplant center after surgery?

Because emergencies happen fast. Rejection, infection, or drug toxicity can turn critical within hours. Nearly 92% of U.S. transplant centers require patients to live within a 2-hour drive for the first year. This ensures you can get to the hospital immediately if your tacrolimus level crashes or you develop sepsis. It’s not a suggestion-it’s a safety rule.

What Comes Next?

The future of transplant care isn’t about stronger drugs. It’s about smarter ones. Researchers are testing ways to train the immune system to accept the new organ without lifelong suppression. Early results with regulatory T-cell therapy show promise. If this works, patients might one day stop all immunosuppressants.

Until then, the focus is on minimizing damage. Steroid-free protocols are now used in 85% of leading centers. New drugs like voclosporin are reducing kidney toxicity. Monitoring is getting more precise. But the core challenge remains: balancing survival with quality of life.

For now, the answer is simple: take your meds. Know your numbers. Speak up about side effects. And never assume you’re fine just because you feel okay. Your transplant is a gift-but it comes with a responsibility that never ends.

Ryan Cheng

December 25, 2025 AT 17:33Man, this post hit hard. I’m 7 years out from a kidney transplant and still taking 10 pills a day like clockwork. The fatigue? Real. The moon face? Still there. But I’m alive. My mom’s not. That’s the trade-off. I don’t complain anymore-I just make sure my labs are on point. If you’re on this journey, you’re already stronger than you think.

wendy parrales fong

December 26, 2025 AT 19:10It’s wild how something that saves your life can also make you feel like a stranger in your own body. I used to hate looking in the mirror. Now I just see the person who fought to be here. That’s enough. I don’t need to look like I did before. I just need to keep breathing.

Jeanette Jeffrey

December 27, 2025 AT 21:18Oh please. You people act like taking immunosuppressants is some heroic sacrifice. It’s just chemistry. You’re a walking drug cocktail. Your body’s not ‘fighting’ anything-it’s being chemically subdued. And don’t get me started on the ‘quality of life’ nonsense. You’re not living-you’re surviving in a lab. At least admit it’s not glamorous.

Shreyash Gupta

December 29, 2025 AT 18:50bro i took st johns wort for 3 weeks after my liver xplant and my tac levels dropped to 0.2 😳 i thought i was gonna die. now i just drink tea and pray. 🙏

Dan Alatepe

December 30, 2025 AT 16:52Y’all ain’t even scratching the surface. I had a 3-day fever after eating raw oysters. They thought I was gonna lose the kidney. They pumped me full of antibiotics, steroids, and IV fluids for 72 hours straight. My wife cried in the waiting room. I lost 15 pounds in a week. This ain’t ‘life-saving’-it’s a daily war with no end in sight. And don’t tell me to ‘stay positive.’ I’m tired. I’m scared. I’m just trying to make it to dinner.

Angela Spagnolo

December 31, 2025 AT 13:10I... I didn’t realize how many people... struggle with the mood swings... I’ve been... crying for no reason... for months... I thought it was me... but... maybe it’s the prednisone...? I’ll... call my team tomorrow... I promise...

Sarah Holmes

December 31, 2025 AT 13:30How is it acceptable that patients are expected to self-manage a pharmacological minefield with no oversight? This is not healthcare-it’s negligence disguised as autonomy. You’re handing someone a life-or-death regimen and then telling them to ‘take their meds.’ Where’s the accountability? Where’s the system? This isn’t empowerment-it’s abandonment wrapped in a motivational poster.

Jay Ara

December 31, 2025 AT 14:51my cousin got a heart xplant last year. he takes 12 pills every day. he cant eat pizza anymore. cant go to concerts. cant even hug his grandkids without a mask. but he smiles every morning. he says its worth it. i dont know how he does it. but he does. and thats what matters.

Michael Bond

January 1, 2026 AT 04:37St. John’s wort and grapefruit juice? Don’t risk it.

Kuldipsinh Rathod

January 1, 2026 AT 17:50Reading this made me cry. I’ve been on tacrolimus for 12 years. My kidneys are fried, my cholesterol’s through the roof, and I can’t sleep without sleeping pills. But I’m here. I watched my daughter graduate. I held my grandson. That’s more than I ever thought I’d get. I don’t know how to fix this system. But I know I’m not alone. Keep going.