Medical Society Guidelines on Generic Drug Use: What Doctors Really Think

Dec, 8 2025

Dec, 8 2025

When your pharmacist hands you a pill bottle with a different name than what your doctor wrote, you might wonder: Is this the same drug? Is it safe? The answer isn’t as simple as it seems - and it depends heavily on medical society guidelines and the specific medication you’re taking.

Why Generic Drugs Aren’t All Treated the Same

Most people assume that if a drug is generic, it’s just as good as the brand-name version. The FDA says yes - and they’re right for most drugs. Generic medications must contain the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They also have to prove bioequivalence, meaning their blood levels fall within 80-125% of the brand drug’s levels. That’s the standard. But here’s the catch: that 80-125% range isn’t a tiny margin. For some drugs, even a small shift in blood concentration can mean the difference between control and crisis. That’s why medical societies don’t treat all generics the same. Their guidelines aren’t about distrust - they’re about precision.Neurology: Why Seizure Medications Are a Special Case

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) has one of the clearest, most firm stances on generics: they oppose automatic substitution for anticonvulsants. Why? Because epilepsy isn’t just a condition - it’s a matter of milligrams and milliseconds. A slight drop in drug levels can trigger a breakthrough seizure. A slight increase can cause dizziness, confusion, or worse. Studies show that nearly 7 out of 10 neurologists have seen patients experience problems after switching to a generic version of drugs like phenytoin, carbamazepine, or lamotrigine. These aren’t rare cases. With 3.4 million Americans living with epilepsy, even a 1% increase in seizure risk affects tens of thousands. The AAN’s position isn’t anti-generic. It’s pro-safety. They want prescribers to make the call - not pharmacists or insurance companies. Many states have laws that reflect this, requiring explicit permission from the doctor before substituting antiepileptic drugs. This isn’t bureaucracy. It’s a safeguard.Oncology: Off-Label Use Makes Generics More Complex

In cancer care, the rules change again. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) doesn’t just accept generic drugs - they actively include off-label uses in their guidelines. That means a generic drug approved for one type of cancer might be used for another, even if it’s not officially labeled for that purpose. Why does this matter? Because 42% of cancer drug uses in the NCCN Compendia are off-label. Insurance companies often rely on NCCN to decide whether to cover a drug. If a generic is listed as equivalent for one use, it’s often covered for another - even if the FDA hasn’t approved it for that specific condition. This creates a unique system where generics aren’t just cheaper alternatives. They’re flexible tools. But it also means doctors have to stay on top of constantly updated guidelines. A drug that was considered interchangeable last year might now be flagged as not equivalent for a new indication. That’s why oncologists don’t just rely on the FDA’s Orange Book - they use NCCN as their real-time reference.

What the AMA and FDA Say About Naming

The American Medical Association (AMA) doesn’t decide whether a drug is safe to substitute - but they do decide what it’s called. Through their United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council, they create nonproprietary names for every generic drug in the U.S. Their goal? Reduce confusion. A bad name can lead to a deadly mistake. Imagine a drug called “Lunovil” being confused with “Lunovex.” Sounds similar. Looks similar. But they’re not the same. The USAN Council avoids stems (the ending parts of drug names) that are too close to others. They also make sure names are easy to pronounce and spell - because if a nurse misreads a prescription, someone could get the wrong drug. The FDA agrees. Their stance is simple: if a drug has an “A” rating in the Orange Book, it’s therapeutically equivalent. But they also know that naming matters. That’s why the USAN Council’s work is quietly critical to safe substitution.Why 90% of Prescriptions Are Generic - But Not Everywhere

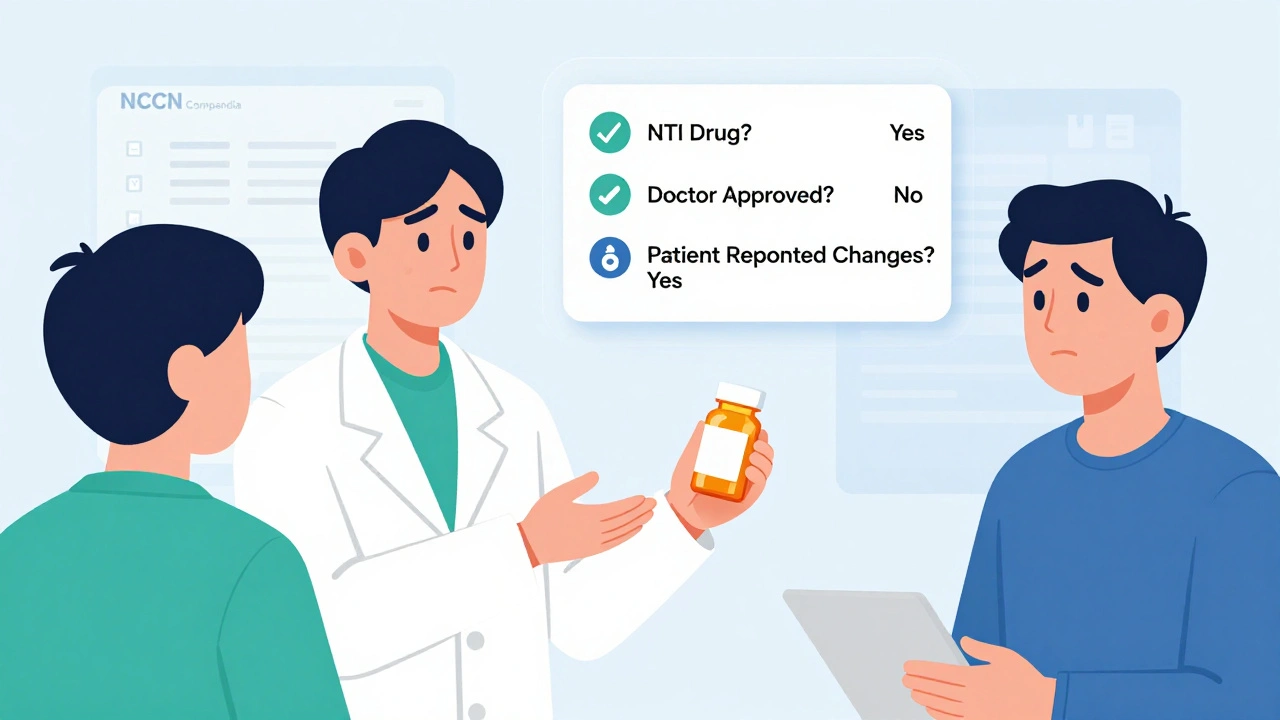

Here’s a number you’ll hear a lot: 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are generic. That’s because they cost 80-90% less than brand-name drugs. For Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers, that’s a massive savings. In 2022, generics made up 90% of prescriptions but only 23% of total drug spending. But that doesn’t mean every doctor is comfortable with substitution. In primary care, where most prescriptions are for high blood pressure, diabetes, or cholesterol, generics are routine. No one bats an eye. In specialties like neurology, psychiatry, or transplant medicine - where drugs have narrow therapeutic indices (NTIs) - things are different. NTI drugs are those where the difference between a therapeutic dose and a toxic one is small. Think warfarin, lithium, cyclosporine, or levothyroxine. Even small changes in absorption can lead to serious side effects. Some states require prescriber consent before substituting NTI drugs. Others don’t. That creates a patchwork of rules. A patient in Texas might get a generic switch without warning. A patient in New York might be protected by law. The inconsistency adds confusion - and risk.

What Patients Should Do

If you’re on a medication that’s been switched to a generic version and you feel different - even slightly - speak up. Don’t assume it’s “in your head.” Ask your doctor: Is this drug on the list of ones where substitution can be risky? If you’re on an antiepileptic, thyroid hormone, blood thinner, or immunosuppressant, the answer might be yes. Also, ask your pharmacist: Is this the same brand I’ve been taking? Sometimes, pharmacies switch generics multiple times - and each new version can behave differently in your body. Keep a log. Note changes in how you feel, your sleep, your energy, your mood, or any new side effects. Bring it to your next appointment. Your doctor can’t help if they don’t know what’s happening.What’s Next for Generic Drug Guidelines

Medical societies are moving toward more alignment with the FDA’s therapeutic equivalence ratings. But they’re not giving up their specialty-specific warnings. The trend isn’t toward blanket approval - it’s toward smarter, more targeted guidelines. The NCCN is adding more off-label uses. The USAN Council is refining naming rules to prevent errors. The FDA is updating the Orange Book quarterly. And state laws are slowly catching up. But the biggest shift? Doctors are starting to talk more openly about this. No longer are they silent on substitution. They’re asking questions. They’re documenting outcomes. They’re pushing back when it matters. It’s not about stopping generics. It’s about making sure they’re used safely - and wisely.Are generic drugs always safe to substitute?

No. While most generic drugs are safe to substitute, medical societies like the American Academy of Neurology caution against automatic substitution for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices - such as anticonvulsants, blood thinners, thyroid hormones, and immunosuppressants. Small changes in blood levels of these drugs can lead to treatment failure or serious side effects. Always check with your doctor before switching.

Why do some doctors oppose generic substitution for epilepsy meds?

Even minor differences in how a generic antiepileptic drug is absorbed can cause breakthrough seizures. Studies show that nearly 70% of neurologists have seen patients experience worsened control after switching generics. Because seizure control depends on very stable drug levels, many doctors prefer to keep patients on the same formulation - brand or generic - to avoid risk.

Do insurance companies force generic substitution?

Yes, in many cases. Insurance plans often require patients to try the cheapest available generic before covering the brand-name drug. But if your doctor writes "Dispense as Written" or "Do Not Substitute" on the prescription, the pharmacy must follow that instruction - even if it costs more. This is a legal right.

How do I know if my drug has a narrow therapeutic index?

Common drugs with narrow therapeutic indices include warfarin, lithium, phenytoin, levothyroxine, cyclosporine, and tacrolimus. Your doctor or pharmacist can tell you if your medication falls into this category. You can also check the FDA’s Orange Book - drugs with an “A” rating are considered equivalent, but those with NTI warnings are flagged in medical guidelines.

Can I request to stay on my brand-name drug?

Yes. If you’ve been on a brand-name drug and it works well for you, you can ask your doctor to write "Dispense as Written" or "Brand Necessary" on your prescription. Many insurers will still cover it if your doctor documents medical necessity - especially for NTI drugs or if you’ve had problems with generics in the past.

Tim Tinh

December 8, 2025 AT 22:03Man, I got switched to a generic for my blood pressure med last month and felt like a zombie for two weeks. Didn't think it was the drug till my cousin told me the same thing happened to her. Now I always ask my pharmacist if it's the same batch as last time. Crazy how much it matters.

Lisa Whitesel

December 10, 2025 AT 07:57Doctors don't care about cost they care about liability. If you have a seizure because you got a different generic it's not the pharmacist's fault it's the doctor's for not writing DAW. End of story.

Philippa Barraclough

December 11, 2025 AT 13:58The nuance here is often lost in public discourse. The FDA's 80-125% bioequivalence range is statistically sound for population-level outcomes, but individual pharmacokinetics vary wildly due to genetics, gut flora, liver enzyme activity, and even meal timing. For drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin, where therapeutic margins are measured in micrograms, this variability isn't noise-it's a clinical signal. Medical societies aren't resisting generics; they're resisting one-size-fits-all substitution protocols that ignore biological individuality. The real issue isn't the drug-it's the system that treats human physiology like a commodity to be optimized for cost.

Larry Lieberman

December 11, 2025 AT 18:36Just got my first generic for my seizure med last week. Felt kinda off but didn't wanna complain. Then I read this and realized I should've asked for the brand. Thanks for the heads up. I'm calling my doc tomorrow.

iswarya bala

December 12, 2025 AT 04:42in india we get generics all the time and they work fine but i know people who switched to us brands and felt way better. maybe its the fillers or something. just listen to your body bro

Courtney Black

December 12, 2025 AT 16:20It's not about trust in generics. It's about the illusion of interchangeability. Two pills may have the same active ingredient, but the excipients-dyes, binders, fillers-can alter dissolution rates, gastric transit, even immune response. In epilepsy, even a 5% shift in plasma concentration can destabilize neural networks. This isn't placebo. It's pharmacokinetics. And the system ignores it because convenience beats caution.

Asset Finance Komrade

December 13, 2025 AT 10:49How ironic that we live in a world where a pill’s name is legally regulated to prevent confusion, yet its efficacy is deemed acceptable within a 45% variance. The FDA’s Orange Book is less a scientific document and more a bureaucratic compromise between corporate lobbying and public health. We’ve commodified medicine to the point that consistency is treated as a luxury. The real crisis isn’t drug substitution-it’s the normalization of therapeutic uncertainty.

Carina M

December 13, 2025 AT 23:23It is profoundly disconcerting that laypersons are expected to navigate the intricate pharmacological landscape of narrow therapeutic index medications without adequate guidance from their primary care providers. The onus should not rest upon the patient to become a pharmacologist merely to avoid iatrogenic harm. The medical establishment’s failure to enforce standardized, non-negotiable substitution protocols for NTI drugs represents a systemic abdication of professional responsibility.

Angela R. Cartes

December 14, 2025 AT 05:27Why do people act like generics are dangerous? It's just chemistry. If it's FDA approved it's fine. You're just scared because it's cheaper. Also, emoji: 🤷♀️

Steve Sullivan

December 15, 2025 AT 15:00Look, I get it-some drugs are finicky. But let's not turn this into a fear campaign. I'm a cancer survivor on a generic immunosuppressant. I've been stable for 7 years. The NCCN guidelines include generics for a reason. If your doctor says it's safe, trust them. If you're paranoid, get a blood test. Don't let marketing scare you into paying 10x more for the same molecule. The system's flawed, but the answer isn't to reject generics-it's to fix the patchwork laws. And yeah, I used emojis because I'm tired of people treating medicine like a religion. 💊