How to Prevent Compounding Errors for Customized Medications

Jan, 14 2026

Jan, 14 2026

When a patient needs a medication that isn’t available off-the-shelf-maybe they’re allergic to dyes, a child needs a tiny dose, or a senior can’t swallow pills-pharmacists step in to make it themselves. This is called compounding. It’s not magic. It’s science. But when done wrong, it can be deadly. In 2012, a single compounding pharmacy’s contamination led to over 60 deaths. Since then, the system has changed. But errors still happen. And they don’t always make headlines.

Why Compounding Errors Happen

Compounded medications aren’t made in big factories with automated machines. They’re mixed by hand, often in small pharmacies with limited staff. One wrong measurement, one misread label, one skipped step-and the dose can be 10 times too strong. Or too weak. Or full of mold. The biggest risks come from:- Calculation mistakes-especially with pediatric or geriatric doses

- Ingredient mix-ups-like confusing lidocaine for fentanyl because both come in small vials

- Poor labeling-concentrations written as ‘per container’ instead of ‘per mL’

- Dirty environments-bacteria or fungi growing in sterile solutions

- Skipping verification-no second pharmacist checking the work

How USP Standards Stop Errors Before They Start

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) sets the rules for how compounding should be done. Two chapters matter most: USP <795> for non-sterile compounds (like creams, liquids, capsules) and USP <797> for sterile ones (like IV bags, injections). These aren’t suggestions. They’re requirements for accredited pharmacies. Here’s what they demand:- Environment control: Sterile work must happen in a cleanroom with ISO Class 5 air quality-like an operating room. Non-sterile work needs ISO Class 8 or better. Dust, skin flakes, and airborne microbes are banned.

- Equipment cleaning: All tools-spatulas, mortars, syringes-must be cleaned and validated after each use. No shortcuts.

- Media fill testing: Every technician who prepares sterile meds must pass a twice-yearly test where they make a fake IV bag under sterile conditions. If bacteria grow in it, they’re retrained.

- Beyond-use dates (BUDs): Every compounded drug has an expiration date, but it’s not printed by the manufacturer. It’s calculated based on testing. A liquid suspension might last 30 days. A sterile injection might only last 6 hours. If the BUD is wrong, the drug could be unsafe.

The Dual-Check System: Your Last Line of Defense

No matter how good the training, how clean the room, or how smart the software-you still need a second pair of eyes. The dual-check system is simple: One pharmacist prepares the medication. A second, independent pharmacist verifies every step:- Does the formula match the prescription?

- Are the ingredients correct? (Check the bottle label, then the lot number, then the certificate of analysis)

- Is the calculation right? (Example: 0.5 mg of levothyroxine in 10 mL of liquid = 0.05 mg/mL)

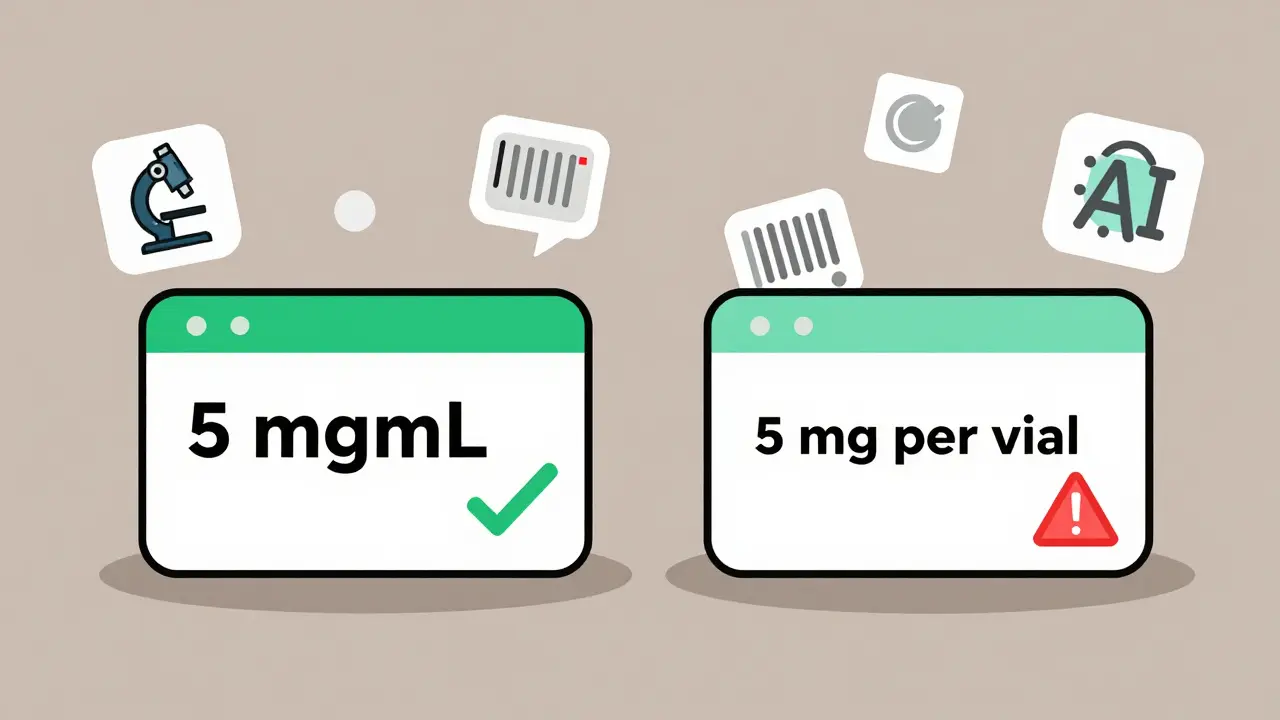

- Is the container labeled correctly? (‘5 mg/mL’ not ‘5 mg per vial’)

- Was the BUD assigned properly?

Technology That Actually Helps

Software isn’t a magic fix-but the right tools make a huge difference. Pharmacies using systems like Compounding.io or PharmScript see a 40% drop in errors. Why? Because these programs:- Auto-calculate doses based on patient weight and desired concentration

- Flag impossible formulas (like trying to dissolve 10 grams of a powder in 5 mL of liquid)

- Require electronic signatures for every step

- Link ingredients to supplier certificates automatically

Accreditation Matters-A Lot

Not all compounding pharmacies are equal. Only about 18% of U.S. compounding pharmacies are accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB). That means they’ve passed a 12-18 month audit. They’ve proven they follow USP standards, train staff quarterly, document every batch, and test their products. A 2022 JAMA Internal Medicine study found error rates varied wildly:- 2% in PCAB-accredited pharmacies

- 25% in non-accredited ones

Labeling: The Silent Killer

In 27 cases between 2018 and 2022, patients overdosed on fentanyl because the label said ‘50 mg per container’-but the prescription meant ‘50 mg per mL.’ One container held 10 mL. That’s 500 mg total. A lethal dose. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now requires all compounded medications to use standardized concentration labeling: ‘mg/mL’, not ‘per vial,’ ‘per bottle,’ or ‘per dose.’ Pharmacists must also include:- The exact active ingredient

- The concentration

- The beyond-use date

- The name and phone number of the pharmacy

What Patients and Doctors Can Do

You don’t have to be a pharmacist to help prevent errors. For patients:- Ask: ‘Is this compounded?’ If yes, ask if the pharmacy is PCAB-accredited.

- Check the label. Does it say ‘mg/mL’? Is the dose what your doctor ordered?

- If it looks different from your last refill-ask why.

- Write clear prescriptions. Don’t say ‘give 0.5 mg.’ Say ‘give 0.5 mg of levothyroxine in 10 mL of oral suspension.’

- Don’t assume the pharmacy knows your intent. Spell it out.

- Ask the pharmacy for a copy of their compounding protocol.

Bottom Line: Compounding Is Essential-But Only If Done Right

Customized medications save lives. They let kids take medicine they can swallow. They let people with allergies get treatment without anaphylaxis. They fill gaps when drug shortages hit. But they’re not safe by default. Safety is built-step by step, check by check, label by label. The tools exist. The standards are clear. The data proves it works. The question isn’t whether we can prevent these errors. It’s whether we’re willing to do what it takes.What is the most common cause of compounding errors?

The most common cause is calculation errors, especially with pediatric or geriatric doses where tiny differences matter. Mislabeling concentration (e.g., ‘per vial’ instead of ‘per mL’) and skipping the dual-check system are also top causes. A 2021 study found 3-15% of compounded medications had significant strength deviations, mostly due to human error in calculations or verification.

Are all compounding pharmacies regulated the same way?

No. There are two types: 503A pharmacies (traditional compounding) and 503B outsourcing facilities. 503A pharmacies are regulated by state boards and follow USP standards, but oversight varies by state. 503B facilities are federally regulated, must follow FDA Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP), and undergo routine inspections. A 2021 study found 503B facilities had a 22% lower error rate than 503A pharmacies due to stricter quality controls.

How do I know if my compounded medication is safe?

Ask if the pharmacy is PCAB-accredited-only about 18% are. Check the label: it must list the active ingredient, concentration (in mg/mL), beyond-use date, and pharmacy contact info. If the dose looks different from your last refill, or if the label is vague, call the pharmacy. Don’t take it unless you’re confident it’s correct.

Can I trust a pharmacy that doesn’t use software for compounding?

It’s possible, but riskier. Pharmacies that rely only on paper records and manual calculations are more likely to make errors. Software like Compounding.io or PharmScript reduces errors by 40% by auto-checking formulas, flagging impossible doses, and requiring digital verification. If a pharmacy doesn’t use any digital tools, ask how they prevent calculation mistakes-and if they use a dual-check system.

Why are beyond-use dates so important?

Beyond-use dates (BUDs) tell you when a compounded medication is no longer safe or effective. Unlike factory-made drugs, compounded ones don’t have years of stability testing. Their BUD is based on scientific data from the pharmacy’s own testing. A non-sterile cream might last 180 days. A sterile injection might expire in 6 hours. Using a drug past its BUD can mean reduced effectiveness or dangerous contamination.

What should I do if I suspect a compounding error?

Stop taking the medication immediately. Contact your pharmacist and doctor. Report the issue to the pharmacy’s quality control team. If you or someone else had a reaction, file a report with the FDA’s MedWatch program. Most pharmacies have internal reporting systems, but the FDA tracks trends across the country. Your report could prevent another incident.

Andrew Freeman

January 14, 2026 AT 16:36says haze

January 15, 2026 AT 09:15TooAfraid ToSay

January 16, 2026 AT 17:22Robert Way

January 18, 2026 AT 08:09Sarah Triphahn

January 18, 2026 AT 17:19Allison Deming

January 18, 2026 AT 19:45Dylan Livingston

January 18, 2026 AT 23:56Anna Hunger

January 20, 2026 AT 22:20Jason Yan

January 21, 2026 AT 09:45