Generic Drug Classifications: Types and Categories Explained

Jan, 29 2026

Jan, 29 2026

When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you might see a generic version of a brand-name drug. But behind that simple label is a complex system that determines how doctors prescribe it, how insurers pay for it, and even how the government regulates it. Generic drug classifications aren’t just labels-they’re the invisible rules that shape every medication decision in modern healthcare.

Why Drug Classifications Matter

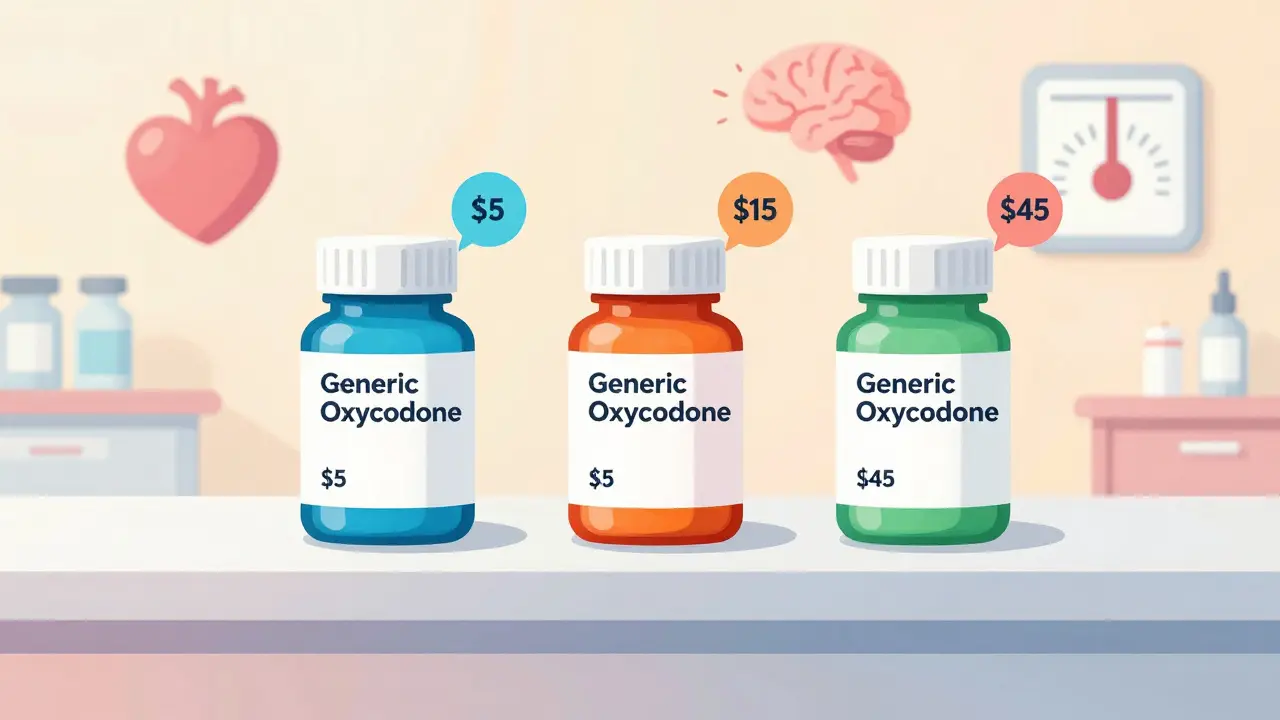

You don’t need to be a doctor to understand why this matters. Imagine two patients with the same pain. One gets a generic version of oxycodone. The other gets a different generic with the same active ingredient. One is covered at $5. The other costs $45. Why? It’s not about quality. It’s about classification. Classifications group drugs based on what they do, how they work, and how risky they are. Without them, prescribing would be chaos. Hospitals wouldn’t know which drugs to stock. Pharmacists couldn’t catch dangerous interactions. Insurance companies couldn’t control costs. The system isn’t perfect-but it’s the only thing keeping thousands of drugs from becoming a tangled mess.Therapeutic Classification: What the Drug Treats

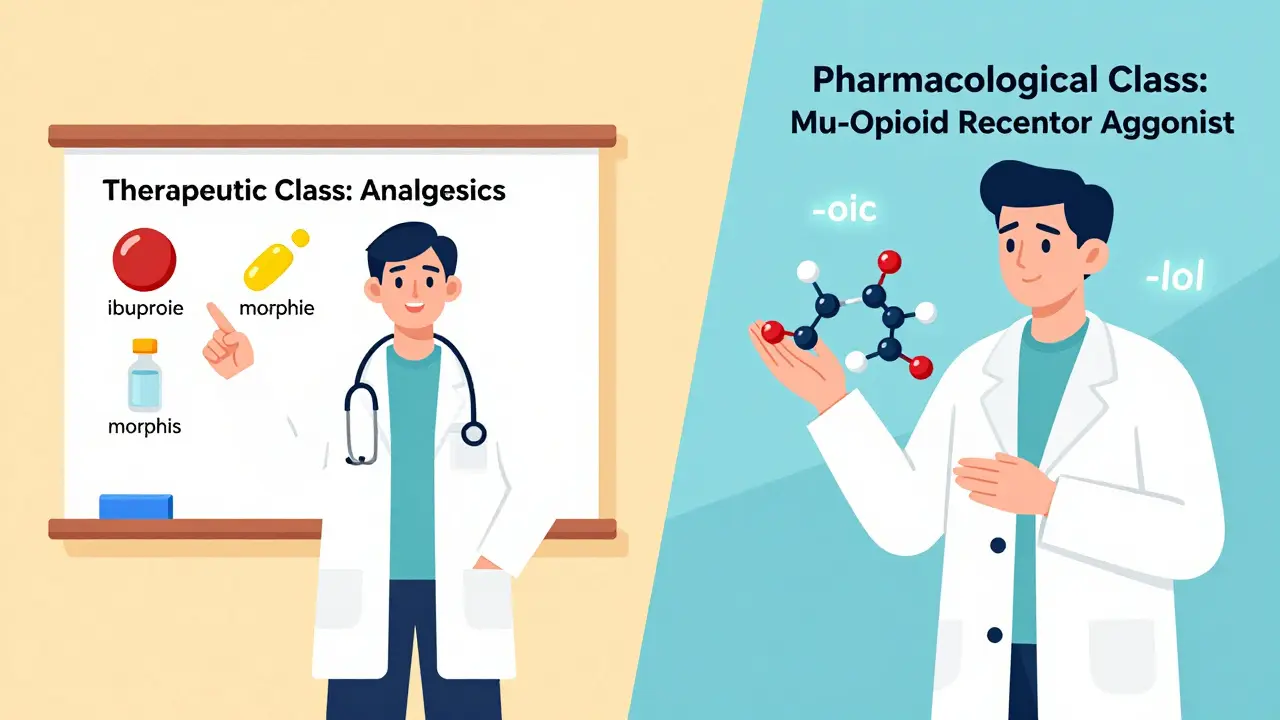

This is the most common way doctors think about drugs. It’s simple: what condition is this for? The FDA and USP use a system called the Therapeutic Categories Model. It breaks drugs into broad groups like:- Analgesics (pain relievers)

- Cardiovascular agents (for heart and blood pressure)

- Antidepressants

- Antibiotics

- Diabetes medications

Pharmacological Classification: How the Drug Works

This is the science side. Instead of asking what does it treat?, this system asks how does it work? Drugs are grouped by their biological target. For example:- -lol drugs (like metoprolol) block adrenaline receptors-beta-blockers

- -prazole drugs (like omeprazole) shut down stomach acid production-proton pump inhibitors

- -navir drugs (like lopinavir) block HIV replication-protease inhibitors

DEA Schedules: Legal Control and Abuse Risk

This is the law’s way of controlling drugs. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) divides controlled substances into five schedules based on two things: medical use and abuse potential.- Schedule I: No medical use, high abuse risk. Examples: heroin, LSD, marijuana (federally)

- Schedule II: High abuse risk, but accepted medical use. Examples: oxycodone, fentanyl, Adderall

- Schedule III: Moderate abuse risk. Examples: ketamine, buprenorphine

- Schedule IV: Low abuse risk. Examples: Xanax, Ambien

- Schedule V: Minimal abuse risk. Examples: cough syrups with small amounts of codeine

Insurance Tiers: What You Pay

This isn’t about science or law. It’s about money. Most insurance plans use a 5-tier system to manage drug costs:- Tier 1: Preferred generics-cheapest, usually $5-$10

- Tier 2: Non-preferred generics-slightly more, maybe $15-$25

- Tier 3: Preferred brand-name drugs-$40-$70

- Tier 4: Non-preferred brands-$70-$100+

- Tier 5: Specialty drugs-often $500+, for rare or complex conditions

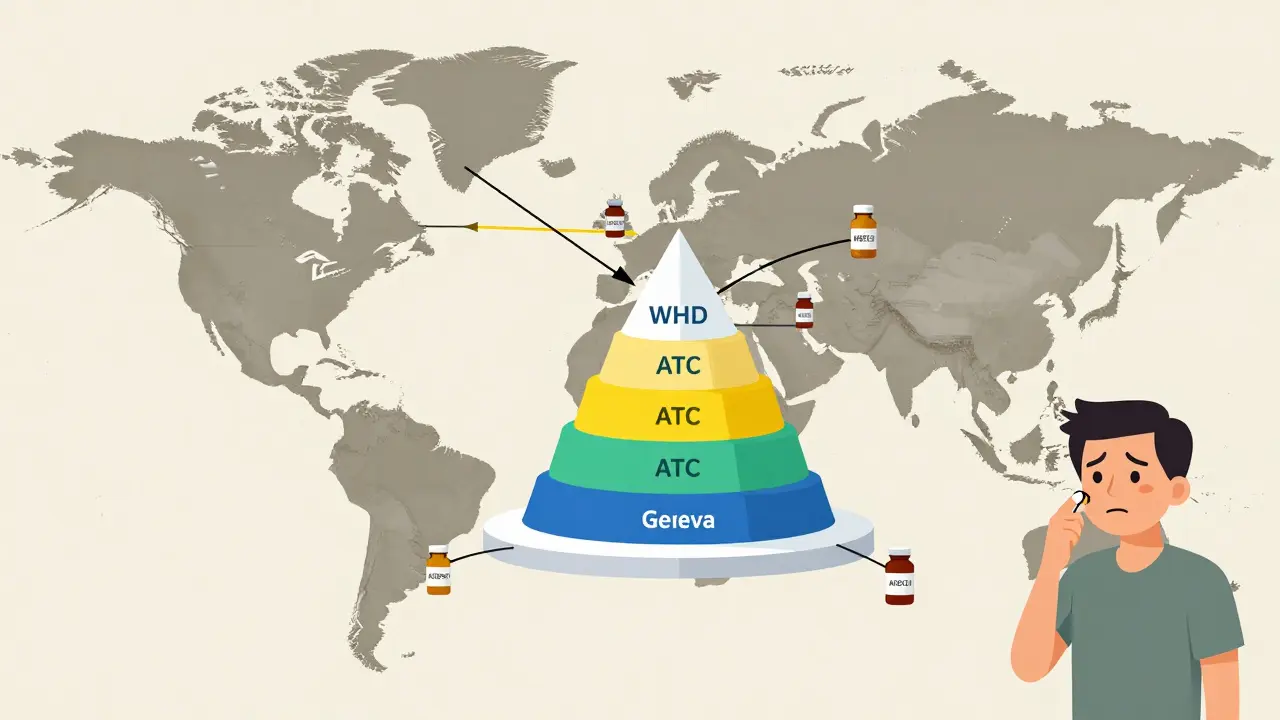

The ATC System: The Global Standard

If you travel abroad, you’ll find that most countries use the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) system, developed by the World Health Organization. It’s like a universal language for drugs. The ATC code has five levels:- Level 1: Body system (e.g., A = Alimentary tract and metabolism)

- Level 2: Therapeutic subgroup (e.g., A02 = Drugs for acid-related disorders)

- Level 3: Pharmacological subgroup (e.g., A02B = Antiulcerants)

- Level 4: Chemical subgroup (e.g., A02BC = Proton pump inhibitors)

- Level 5: Chemical substance (e.g., A02BC01 = Omeprazole)

Stem Naming: The Hidden Clue in Drug Names

Ever notice how many drug names end in the same few syllables? That’s not random. It’s a secret code. The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) created a naming system in 1964. Drug names include “stems” that tell you the class:- -lol = beta-blocker (metoprolol, atenolol)

- -prazole = proton pump inhibitor (esomeprazole, pantoprazole)

- -tidine = H2 blocker (famotidine, ranitidine)

- -navir = HIV protease inhibitor (atazanavir, darunavir)

- -cept = monoclonal antibody (adalimumab, infliximab)

Why the System Is Broken (And What’s Changing)

The problem isn’t that these systems exist. It’s that they don’t talk to each other. A doctor uses therapeutic classification to pick a drug. The pharmacist checks DEA schedules for legal limits. The insurance system pushes a cheaper generic from Tier 2. The patient gets confused. The record system flags a conflict because the drug is listed in three different categories. Healthcare workers waste hours sorting through conflicting data. One study found that primary care doctors spend 12-18 minutes per patient just trying to reconcile classification mismatches. The FDA is trying to fix this. In 2023, they launched Therapeutic Categories Model 2.0. This new version lets drugs have a primary and secondary indication. So aspirin can be listed as both an analgesic and an anticoagulant. No more forced choices. Meanwhile, AI tools like IBM Watson’s Drug Insight platform are learning to predict the best classification based on patient data. Early results show 92.7% accuracy. The future won’t have one system. It’ll have layers-therapeutic, pharmacological, legal, financial-all linked together. But that’s still years away.What You Need to Know

You don’t need to memorize all this. But you should understand a few things:- Just because a generic is cheaper doesn’t mean it’s better-it just means your insurer negotiated a better deal.

- Two generics with the same active ingredient can be on different insurance tiers. Ask your pharmacist why.

- If a drug has a name ending in -prazole, -lol, or -navir, you can guess its class without looking it up.

- DEA schedules control how you get the drug, not how well it works.

- Therapeutic classification is what your doctor uses. Everything else is behind the scenes.

What is the difference between generic drug classifications and brand-name classifications?

There’s no difference in classification. Generic and brand-name drugs with the same active ingredient are placed in the same therapeutic, pharmacological, and DEA categories. The difference is in cost, packaging, and insurance tier placement-not in how they’re classified. A generic oxycodone and brand-name OxyContin both fall under Schedule II, opioid analgesics, and are classified as mu-opioid receptor agonists.

Why are some generic drugs more expensive than others?

It’s not about the drug-it’s about insurance contracts. Two identical generic drugs can be on different insurance tiers. One might be in Tier 1 (preferred) because the insurer has a deal with that manufacturer. The other is in Tier 2 (non-preferred) because no deal exists. The pill is the same. The cost isn’t.

How do I know if a drug is a beta-blocker?

Look at the generic name. If it ends in “-lol,” it’s almost certainly a beta-blocker. Examples include propranolol, metoprolol, and atenolol. This naming rule is part of the USP stem system and helps doctors and pharmacists quickly identify drug classes.

Is marijuana classified as a Schedule I drug?

Federally, yes-marijuana is still classified as Schedule I by the DEA, meaning it has no accepted medical use and high abuse potential. But this is controversial. The FDA has approved marijuana-derived drugs like dronabinol (Schedule II) and Epidiolex (Schedule V). Many states allow medical use, and federal law may change. The classification doesn’t reflect current medical evidence.

Do all countries use the same drug classification system?

No. The U.S. uses a mix of therapeutic, DEA, and insurance-based systems. Most other countries rely on the WHO’s ATC system, which is more standardized and globally recognized. The ATC system is used in 143 countries and is the backbone of international drug data sharing.

Can a drug belong to more than one classification?

Yes-and increasingly so. Drugs like duloxetine treat both depression and nerve pain, so they’re classified under both antidepressants and neuropathic pain agents. The FDA’s new Therapeutic Categories Model 2.0 allows primary and secondary classifications to handle these multi-use drugs better than older systems.

Rob Webber

January 29, 2026 AT 18:19calanha nevin

January 29, 2026 AT 19:05Claire Wiltshire

January 30, 2026 AT 09:14Darren Gormley

January 30, 2026 AT 16:13Sidhanth SY

January 31, 2026 AT 07:27Beth Cooper

January 31, 2026 AT 15:48Donna Fleetwood

February 2, 2026 AT 07:31Bobbi Van Riet

February 3, 2026 AT 22:14Carolyn Whitehead

February 4, 2026 AT 03:02Natasha Plebani

February 4, 2026 AT 10:00Kelly Weinhold

February 6, 2026 AT 08:24Kimberly Reker

February 6, 2026 AT 17:53